You Don’t Have IBS, You Have An Eating Disorder

But why not both?

Welcome to The Ick, Season 4: DISGUST. The season will culminate in a print magazine and live reading in San Francisco. Subscribe here so you don’t miss event info and updates! Every paid subscription helps us cover printing costs.

Today’s article is from me, Emily, and it’s definitely a disgusting subject. Content warning: gut stuff, eating disorders.

Making mayonnaise is disgusting.

I learned this in 2021, when I was pouring olive oil directly into a blender. As I looked down into the spinning blades, I was forced to acknowledge mayo is just a fatty goop made entirely of oil and egg. Watching it emulsify into milky slime, I felt sick.

I’d been feeling sick since I was 18, actually. I was battling crippling bowel distress caused by a long list of possible allergens. Flare-ups would blindside me without pattern or warning. By the time I was 21, I’d had more colonoscopies than most middle-aged men, and still the diagnosis came back null. Well, not null exactly. My chart said IBS, irritable bowel syndrome, but this diagnosis is functionally meaningless.

On this day in 2021, I was finally allowed to eat eggs. I was one week into an elimination diet, testing for food allergies, and eggs had just been cleared for reintroduction.

That’s how I found myself making mayonnaise from scratch. Elimination diets work by cutting out all major allergens—soy, dairy, gluten, etc—then adding them back one at a time to see how the body responds. The early phase was brutal: mostly rice and meat, a few plain vegetables and fruits, and absolutely no sauces, spices, condiments, or sweets. The preservatives and additives in store-bought brands like Hellman’s would pollute the experiment. The goal was to keep the data clean and variables low.

In the end, though, I didn’t determine any new allergies. My symptoms returned. This might seem like a failure. But in a strange and backwards way, I healed something else: my eating disorder. And I became an evangelist for gut science.

Everyone has IBS now

IBS is problematic because it's poorly understood and difficult to diagnose. There is no biological marker. It is diagnosed by symptoms only, so many people labeled with IBS are actually suffering from a different condition with overlapping symptoms.1

Women seem to be especially susceptible. A global meta-analysis found women had ~50 percent higher odds of IBS than men. Correlation and causation are a mess, notably in women with eating disorders who frequently experience other related conditions such as anxiety and depression.

Many people with IBS, like me, experience a sudden onset of symptoms in early adulthood. In my 20s, I ran the gauntlet with gastroenterologists, nutritionists, dieticians, and allergists to find a cure. I was prescribed psyllium husk, loperamide, probiotics, antibiotics, cholestyramine, depression meds—but nothing worked for long.

In my 30s, I talked to a friend who had sudden digestive turmoil similar to mine, and hers turned out to be parasites. She gave me the name of her practitioner, Dr. M, and I called right away. Dr. M specialized in uncommon causes like tapeworms, Candida yeast overgrowth, and parasites—things my Western medicine providers had never tested for.

She had me try things that felt refreshingly unconventional. I sent a bowel sample to Kenya. I got my DNA sequenced. I had the colors and textures of my tongue analyzed. I tried acupuncture and Chinese herbs. I learned about doshas and ate according to Ayurveda. I drank two gallons of white oak bark tea every week. Much of the work we did together was to “starve” the possible tapeworm or “bad” bacteria. Over time, I began to see my gut as a battlefield, invaded by aliens and toxins, and I was losing.

Reader, I did not have a tapeworm.

After a full year with Dr. M, she told me bluntly: “I’ve tried everything. There’s nothing else I can do.” She gave me the name of a hypnotherapist, “You’re probably just stressed.”

Is it stress?

I took the name of the hypnotherapist, but I was bitter. I felt blamed and alone. I went to one hypnosis appointment, but the therapist was a little too keen on Joe Dispenza and past-life regression. I didn’t go back.

Meta-analyses estimate 14 percent of people globally suffer from IBS. Are these hundreds of millions of people “just stressed”? Is IBS just all in our head?

“The answer is yes,” writes Natasha Boyd in The Drift, “once you realize the head is also in the stomach.”

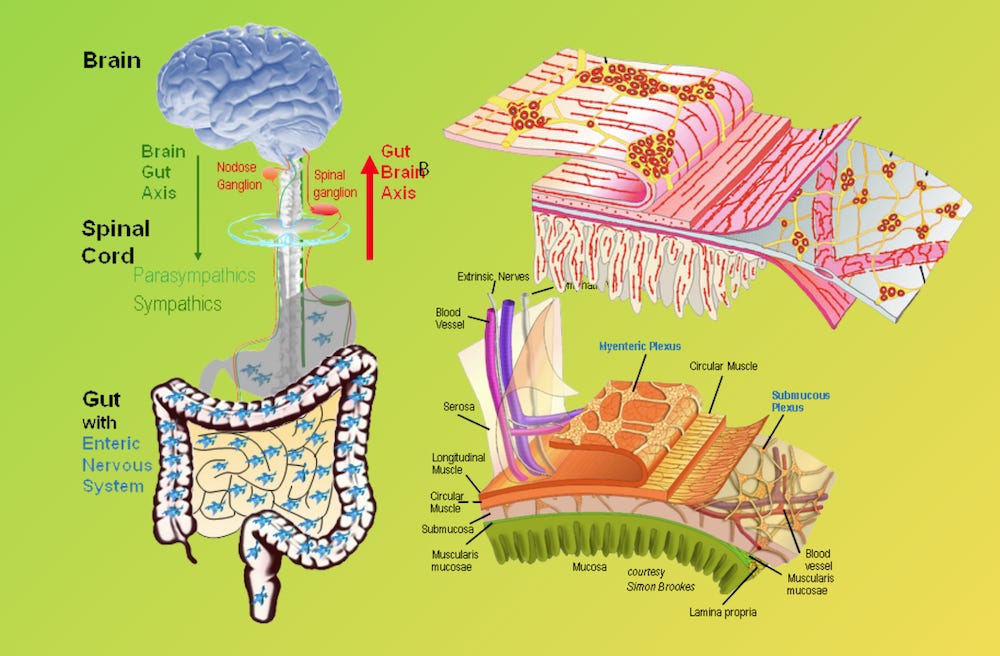

You’ve probably heard that the gut is your second brain. But “second brain” isn’t exactly right. The gut is a neurochemical command center that interacts with the brain as a peer.

Understanding this really rocked my sense of body and self. I used to roll my eyes at Dr. M when she urged me to “meditate with my gut”. “Put your hands on your belly,” she said, “and ask it, ‘What are you trying to tell me?’” It sounded absurd, until I learned how much the ENS operates outside of conscious awareness.

The walls of our gastrointestinal tract are latticed with 100–500 million neurons, collectively called the enteric nervous system (ENS). This network coordinates gut motility, pain signaling, and inflammatory responses without any input from your “main” brain. It’s effectively an autonomous nervous system for digestion, tuned to monitor what’s happening inside our gut and decide what signals to send upstairs to the grey matter. And where do these neurons get their information? From the trillions of microbes living in your intestines.

There are approximately 30 to 40 trillion microbes in the digestive tract—nearly equal to the number of human cells in the body. They are so deeply wired into gut-brain communication that scientists now consider these microbes co-authors of our moods, cravings, even our personality.

Bacteria are determining my personality? Give me a break, right, I know. But consider that the gut is responsible for synthesizing key mood-regulating neurochemicals (~90 percent of the body’s serotonin is made in the gut!). And new science is finding conditions like depression, anxiety, acne2, Schizophrenia, and Alzheimer's3 have distinct microbiota signatures. Our microbiome is in charge of our happiness, our sadness, maybe even our cognitive resilience or decline.

So how is stress involved? Cortisol is the main culprit. Stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system, triggering a cascade of hormones—cortisol chief among them. Cortisol binds to glucocorticoid receptors, causing changes in the proteins that normally seal the gut lining. When these tight junctions loosen, the gut becomes more permeable (commonly called “leaky gut” a truly disgusting phrase, sorry), letting bacteria, toxins, and undigested particles pass into the bloodstream, triggering inflammation.4

In parallel, stress disrupts the balance of microbes themselves. The inflammatory response decreases diversity and encourages the overgrowth of harmful bacteria (“dysbiosis”).

So yes, stress precipitates and perpetuates IBS symptoms. For me, the constant search for the cause—what am I doing wrong? too much sugar? not enough fiber? too many FODMAPs??—created a vicious cycle of food restriction and body dysmorphia.

It might not surprise you that 90 percent of women with eating disorders are diagnosed with IBS. This is the part left unsaid in the sardonic meme “hot girls have stomach issues”. Correlation or causation is uncertain, but the theory is that eating in disordered patterns disrupts the balance of gut flora. And the stress associated with hyperfixation around food or body image leads to further gut disruption.

Eating disorder or whatever

I have never been clinically diagnosed with an eating disorder. Different psychotherapists have raised the alarm over the years, but I’ve never been medicated or hospitalized. Eating disorders are a spectrum, with “worried about ice cream” on one end, and “food obsession and social isolation” on the other. I’ve slid around on the spectrum a lot in my life, but by 2021, as I was making mayonnaise in my kitchen, I was in a very bad place.

Coming of age in the early 2000s was brutal for my body image. If you didn’t live through it, let me give you a snapshot of the climate. America was experiencing a collective anxiety attack about obesity. After decades of rising rates of heart disease and type 2 diabetes, fat had become a public enemy. Nutrition science was blindly groping around for the cause—oh, it’s saturated fats, oh no actually it’s LDL cholesterol, nope scratch that it’s carbohydrates—stoking confusion and panic. Meanwhile, the diet-industrial complex was making billions. Our moms microwaved Lean Cuisines and refused cake at our birthday parties. Schools were federally mandated to remove whole milk and vending machines from the cafeteria.

In 2001, I was a ballet dancer who watched a lot of America’s Next Top Model. I was doomed.

I didn’t recognize it at the time, but I was binge eating. Food thoughts dominated my day, dictated my mood, and isolated me socially—red flags that indicated I was moving along the spectrum from “disordered eating” to “eating disorder”. However, these feelings about food were always tied, confusingly, to my allergies.

“Good” foods, I thought, were rainbow vegetables and leafy greens full of fiber. Healthy and nutrient-dense. Who could be allergic to “good foods” like that? “Bad” foods were carbs and fat: baked goods, oily meats, full-fat dairy, all sugars.

I was constantly “body checking”—a behavior I now know is characteristic of body dysmorphia—scrutinizing my different body parts in the mirror, back of the arms, stomach, thigh circumference, to see if they were bigger or smaller than a few hours ago. I was binge eating “good” foods to the point of making myself sick, and depriving myself of “bad” foods. I was racked by cravings I would never satisfy. By day I would eat raw vegetables, tuna salads, coleslaw, and beans. (I learned later that raw veg and high fiber are extremely aggravating to an inflamed gut.) I sugar fasted and juice fasted. I villainized high glycemic fruits like bananas and grapes. I remember eating three bowls of low-fat granola and skim milk one night in the darkness of the kitchen, unable to stop. Or the time I had two huge bags of baked potato chips in bed, trying to fill my deep craving for something more filling.

In addition to all these complicated feelings around food, my digestion was completely out of control. Flare ups would send me running to the bathroom 20 times a day, cripple me with bloating and cramps, and prevent me from leaving the house for long, let alone traveling. Feeding myself was a ferment of confusion and shame. I blamed myself, assuming my symptoms were caused by lack of self-control. But no matter how strictly I ate according to my “good” food guidelines, my stomach continued to act up, and my body size continued to repulse and disappoint me.

Many people with eating disorders have it worse than me. I hid my symptoms enough socially that my disordered eating mostly went unnoticed. Although my weight fluctuated in amounts that were excruciating to me, it was never enough for friends or family to intervene. Not being clinically diagnosed wasn’t the most stigmatizing, but it was the most invisible. I had to deal with the stress of hating my body and not knowing how to eat all in relative silence. It was, and remains, very lonely.

Elimination diet recovery

So, anyway, the mayonnaise.

In 2021, I was obsessing over my post-pandemic weight gain. Body dysmorphia was crowding every thought. And my gut was waging all-out mutiny. I was looking frantically for interventions I hadn’t tried, picking up and putting down various diets like low-FODMAP and keto. Then I read about small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and remembered drinking gallons of tree bark tea with Dr. M to kill off Candida yeast. Maybe it was more than just one bad guy. Maybe my whole population needed a reset.

I found a nutritionist specializing in gut biome and digestive system repair. We would start with an elimination diet to lower inflammation and determine any allergies. “But,” the practitioner said to me, “don’t lose weight.”

I blinked at her.

“That’s not the goal, in fact that could undermine our progress,” she said. “We’re working on finding digestible, nourishing foods that your body can absorb. This is not about weight loss.”

She listed off high-calorie, low-inflammatory foods to help me increase my caloric intake during the first few weeks: avocados, olive oil, coconut oil, rice, potatoes... But her voice muted and fell away as I tilted backwards. I gripped the edge of the table. I felt a wave of vertigo and nausea. I’d only ever wanted to lose weight. Every thought I’d ever had about my body or food since I was 12 or 13, since I started ballet, since my boobs came in, since I became interested in boys, was about being thinner. The goal had always been loping along behind me, clipping my heels. One could, I’d been taught, always lose a few pounds.

I cleared my throat. “Wait, sorry…”

I had her explain it again. I tried to relax into it, tried to hear her words as medicine, as prescription, as permission.

Over the course of the next six months I shifted my goal, for the first time in my life, to eating foods with calories. With disordered eating and body dysmorphia, there is no single, magical cure. But this approach radicalized me. I started checking on myself from the inside first—whether my digestive tract felt energized, sluggish, crampy, or cozy—instead of from the outside, in the mirror, measuring my belly and bloat.

Still, pouring a whole bottle of oil into the blender was hard.

I knew making all of my own food from scratch would be time consuming and labor intensive. But I didn’t expect to confront so many deep-seated beliefs. I didn’t think I had an eating disorder! I didn’t recognize my relationship to calories and thinness as toxic; I truly thought this was how most women felt. These beliefs had been normalized and reinforced by every media message and beauty standard growing up. Plus, so many women in my life—peers, friends, and adult role models alike—talked about food with the same moral valence. “Oh I’m gonna be bad and have another slice!” “Oh this guacamole is too good, I shouldn’t!” No one had ever challenged my binary thinking until this moment.

As I made my own mayonnaise, ground my own almond butter, and baked my own granola, I had to face their sugar and fat content. This was deeply frightening. It sounds crazy to have visceral fear of a food group, but that’s really how it felt: dread, terror, panic. I had to train myself to look at the monster under the bed and see it as just a pile of clothes. I began to recognize fat and carbs for what they really were—macronutrients—not an enemy or a moral failing. Oil, butter, and sugar make these foods satisfying, satiating, and nourishing, in a way that baked potato chips could never.

Integrating “forbidden foods” slowly and steadily is a therapy modality for eating disorders, but I did not know this at the time and my nutritionist wasn’t doing this intentionally. It happened below my conscious understanding. As I allowed myself to eat and be nourished by foods that used to be off-limits, I felt a new liberty and equanimity. Every huge bowl of rice or entire avocado was slowly teaching me that food could be safe. My body was something to take care of, not fight against. My gut biome needed help, not punishment.

It sounds romantic because I’m romanticizing it. In truth, I had no idea my belief system was transforming—I was just pissed off. I was whiny, frustrated, flipping through pathetic recipe cards from my nutritionist for soy-free fried rice and tomato-free pasta sauce. The light of the world had dimmed. I spent a whole month without coffee or chocolate for chrissakes.

My desperation for flavor during the elimination diet’s austerity pushed me into unexpected terrain. I poured my focus into how to cook meals that tasted good and kept me full, instead of which foods kept me thin. I got really good at cooking, honestly, which was an awesome, if hard-won, side effect. I don’t recommend this method for anyone trying to heal disordered eating. It was risky, in hindsight, to trade one form of restriction and hyperfixation for another. But for me, it scrambled the signal enough to help me rewire.

In the end, this practitioner couldn’t fix me. There is a lot we don’t know about the microbiome, and gut science has a long way to go.

“Studying the microbiome is incredibly challenging,” writes Abhishaike Mahajan, author of Owl Posting. “You’re trying to observe a living, breathing ecosystem that will react to the most minute of perturbations, has an astonishing level of diversity, and can entirely change from day-to-day.” (If you’re curious, you must read Mahajan's full article, which gives a much better analysis of the field and its limitations than I ever could.)

Perhaps this nutritionist was overconfident. Perhaps I was just an impossible case. Unfortunately, I still struggle with IBS flare ups, but a lot has changed. I have a radically different relationship with food and body image. And I have immensely more knowledge, curiosity, and sensitivity about all the trillions of microbes living in my gut.

Me, myself, and my microbiome

The science exploring the gut-brain axis is still new and a bit spooky.

Learning about it has collapsed the mind-body dualism I’ve long held as an anchor. “Me” and “my gut” are not separate entities. My moods, thoughts, even my sense of self, are not confined to the grey matter of the brain. They are co-authored by trillions of microbes and the electric tangle of neurons in my intestines. The hormones and immune responses are animating me without ever forming a conscious thought.

Dr. M was right to recommend “meditating with my gut.” She was urging me to listen to my enteric nervous system, and tune in to the subtle, somatic signals I usually ignore. She understood that the “second brain” ENS operates largely outside of awareness, and that meditation might help me hear what it had to say. I haven’t gained full gut-brain axis enlightenment yet, but I’m working on it.

Even though I’m not cured, I’m optimistic about the field of gut science. Things like fecal microbiota transplants, psychobiotics, and nutritional psychiatry are making incredible strides. Gastroenterology is taking the gut-brain axis seriously, looking at it holistically, and exploring how the microbiome can affect and improve neurological function. Could we treat depression, anxiety, Alzheimer’s—and eating disorders—by adjusting the gut biome? The possibility is there, and I’m hopeful.

I’ve done a lot of work to understand there are no “good” and “bad” foods. I believe the same is true for bacteria. Both food and bacteria are neutral. It’s the balance and the context that matters. The trillions of microbes inside me are not alien or toxic. They are an ecosystem. They are me. And that’s a comfort.

I’m powered by a pantheon of experts working toward our collective survival. And when I think of it this way, I feel a lot less stressed.

You’re reading The Ick, Season 4: Disgust—exploring what makes us recoil and why. This time, it’s not just me: I’ve invited a brilliant cast of writers and friends to share their disgusting POVs. Season 4 will culminate in a print magazine and live reading in San Francisco. Help us offset printing costs by subscribing ($0-$250).

Catch up on past seasons of The Ick here: season 1 embarrassment, season 2 the senses, season 3 etiquette.

Systematic reviews show that among patients meeting IBS criteria, ~41% have bile-acid malabsorption, ~50% have carbohydrate malabsorption (lactose/fructose intolerance), ~49% test positive for small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth. The overlap of GI symptoms (pain, bloating, diarrhea/constipation) with those of ulcerative colitis, celiac, and Crohn's disease also contributes to confusion.

You gotta read about the “gut-brain-skin unifying theory”—it’s so interesting, but a rabbit hole I didn’t have time to explore in this article. “The ability of the gut microbiota and oral probiotics to influence systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, glycemic control, tissue lipid content and even mood itself, may have important implications in acne.” See: “Acne vulgaris, probiotics and the gut-brain-skin axis” (2011)

Distinct microbiotic signatures have been recognized in patients with depression, anxiety, OCD, PTSD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and dementia. See: “Gut microbes in neurocognitive and mental health disorders” (2020) and “Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease” (2017)

“IBS is a stress-sensitive disorder” Cortisol affects mast cells (involved in allergic and inflammatory responses), enterochromaffin (EC) cells (which release serotonin), and lymphocytes (white blood cells) in the gut. In response to cortisol, these cells release neurotransmitters like serotonin and histamines that can activate and regulate the immune system of the gut lining.

Whenever I’m around that generation of women who eats low-fat dairy, I wonder where they find joy in this world. Low-fat dairy is a metaphor for how not to live, I think. It is sad. Maybe we should all eat full fat everything and enjoy it.

Hi! A lot of your IBS experience overlaps with mine, and I know how frustrating people's suggestions can be, but just wanted to share that I saw a functional doctor to see if my hormones were playing a role in this (I long suscepted they might be) and turns out my progesterone was too low every month which was causing an estrogen dominance effect, leading to all sorts of digestive issues. I've been taking bio-identical progesterone for 6+ months with DIM/CDG and it's been seriously transformative for my gut health. Perhaps something you can explore! Wishing you the best.