How I Got Canceled by the Left and Right

What cancel culture reveals and conceals about redemption

Welcome to the season finale! After four months of amazing articles, The Ick Season 4: DISGUST closes with a harrowing essay from Lydia Laurenson.

Over her career reporting on sex, spirituality, and social justice, Lydia has ventured back and forth across the political spectrum. In the 2000s, she built a following blogging about gender and feminism under the name Clarisse Thorn, then branched out to journalism in outlets like The Atlantic and Vice. In 2022, she was briefly engaged to Curtis Yarvin, a central figure in the right-wing neo-reactionary movement (her article Why I Was Part of the Dissident Right is a must-read). How does one person make such a swing from left to right?

In this article, Lydia reflects on how the search for ideological belonging got her cancelled on multiple fronts—and the implications this holds for anyone trying to find connection or redemption in a polarized world.

The first time I was “canceled” was in 2011.

I’d been writing about sex-positive feminism under the name Clarisse Thorn. The feminist movement was transforming: the forces we now call “social justice warriors” and “wokeness” were emerging, yet unnamed. “Cancel culture” was not so well-dissected as it is now, but it’s a long-running phenomenon. We referred to it as “call-out culture.” The blogger Ariel Meadow Stalling wrote a great post about it in 2012, titled “Liberal bullying: Privilege-checking and semantics-scolding as internet sport.” (That title encapsulates so much about the phenomenon.) But the movement was not yet dominated by any of these things.

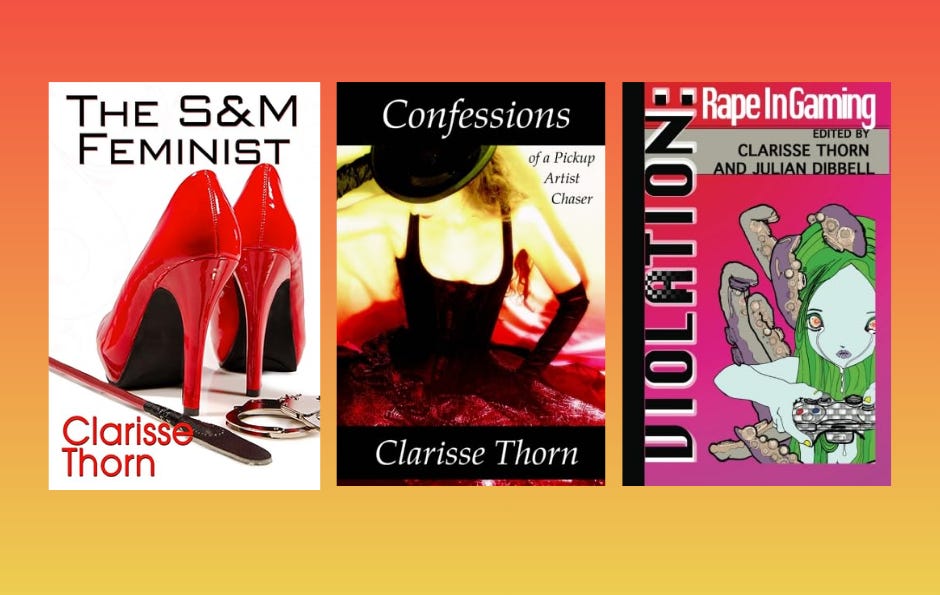

As Clarisse, I wrote primarily about BDSM and sexuality. In my personal life I was trained as a rape crisis counselor1 and I served in the Peace Corps, but I mostly didn’t write about those experiences, even though I was a feminist writer. As Clarisse, I wrote primarily about sex. I focused on consent theory, communication strategies, and my personal experience of fringe sexual practices. I tried to reconcile feminist theory with BDSM practice. At the time, this was difficult and controversial. I took occasional forays into so-called “men’s issues” and I wrote a book about pickup artists. I maintained my pseudonym because it was quite edgy to write directly about sex, especially my own sex life, so I was concerned about being publicly outed for my writing.2

My main goal was to share my honest explorations of the most complex and traumatic territory we navigate as humans, because I believe there are good things to be found there.

I started posting as Clarisse in 2008. That same year, a sex-positive feminist anthology came out, Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape.3 I still think about its introduction 17 years later. The introduction started with Margaret Cho describing how she was raped in high school. Then she wrote these words, and I still tear up when I read them:

[My boyfriend after the rapist] made me feel so beautiful that I could start to see it, too. I learned to love sex and love myself and I grew up and became exactly what I wanted to become and I don’t go to high school reunions. Ever.

My past haunted me still, but it came to me in strange ways. I am surprised by how much sex I have had in my life that I didn’t want to have. Not exactly what’s considered “real” rape, or “date” rape, like my first time, although it is a kind of rape of the spirit—a dishonest portrayal or distortion of my own desire in order to appease another person—so it wasn’t rape at gunpoint, but rape as the alternative to having to explain my reasons for not wanting to have sex. You do it out of love sometimes, to save another’s feelings. And you do it out of hate sometimes, because you don’t want to hear your partner complain—like you hate their voice so much that whenever you aren’t made to hear it, it is a blessing. This is all sex I have said yes to, and sometimes even initiated—that I didn’t want to have. Often I would initiate the encounter just to get it over with, so it would be behind me, so it would be done. It is the worst feeling; it is like unpaid prostitution, emotional whoring. You don’t get paid in dollars, you get paid in averted arguments; you get paid by being able to avoid the truth another day. You hold your breath and you don’t feel your body, and you just let go of yourself. Your body responds just enough to make them think that you are into it, that you want it, that this is really sex. But it isn’t. I hate it, but I have done it, and I really don’t ever want to do it again because it is dehumanizing and demoralizing.

I said yes because I felt it was too much trouble to say no. I said yes because I didn’t want to have to defend my “no,” qualify it, justify it—deserve it. I said yes because I thought I was so ugly and fat that I should just take sex every time it was offered, because who knew when it would be offered again. I said yes because I believed what the kids at school told me—that the only way I could get laid was to be raped. I said yes to partners I never wanted in the first place, because to say no at any point after saying yes for so long would make our entire relationship a lie, so I had to keep saying yes in order to keep the “no” I felt a secret. This is such a messed-up way to live, such an awful way to love.

So these days, I say yes only when I mean yes.

The sex-positive feminist movement shared the ideal that we could recover from this awful sensibility, the internalized degradation Cho named so well. It’s strange to think of that era now, from the vantage of 2025. I’ve heard people say that sex-positive feminism ultimately dominated American culture. I totally disagree. What we have now is very far from healthy sexual culture; sexual culture in 2025 does not feel feminist to me, nor positive. A certain kind of sex is certainly more in-your-face than ever, but I never felt like sex-positive feminism “won,” not in the ways that we dreamed about.

I wanted more healthy exploration and sharing, for everyone, but especially for women. My writing as Clarisse Thorn helped some people find that in their own lives, and I’m grateful for that. But oh, it is so tragic and terrible to see where my country is now, especially when it comes to gender, sex, and relationships.

So that was why I was so passionate about the sex-positive feminist movement. Some people learn about my work at Clarisse and are disgusted. Despite the many attempts to shame me for it, I am not ashamed. A huge part of me, maybe most of me, still loves feminism and roots for its success—despite other parts of me becoming conscious, oh so conscious, of its drawbacks.

Baby’s First Cancellation

By 2011, I’d been writing under the name Clarisse since 2008. I knew my way around feminism, or so I thought.

However, it upset me that the movement kept canceling people. I didn’t think everyone who was canceled deserved it, but some of my friends did. I complained about it privately and my feminist friends kept talking me down.

I learned all the relevant arguments backwards and forwards. Didn’t I want women to be safe and free? Didn’t I want accountability for predators? Of course I wanted those things. So I kept my mouth shut as the problems of cancel culture mounted.

What bothered me most was that there seemed to be no grace, no possibility for a canceled person to recover or make amends—not even anything resembling a “fair hearing” that a person could request once targeted by the cancel mob. Additionally, the cancellation process seemed unfairly harsh for any but very serious crimes. In other words, cancellation struck me as a punishment that didn’t fit most crimes it was used for. Moreover, even when applied to bad cases, the process seemed counterproductive for the community using it; most people who’d been canceled shifted away from social justice norms or left the movement entirely, and sometimes took their friends with them. All these effects seemed destructive and wrong, but saying anything publicly was clearly dangerous for one’s reputation and sanity.

Then the forces of cancellation came for someone I knew. He had done some awful things, but had also publicly written about his regrets, and about efforts to make up for those past actions. I finally took a stand, saying that I thought cancellation was messed up. My core questions were: “Do you believe people can change? And if you do believe it, then how would you help someone change?”

When I wrote that, I was angry. I felt like I was about ready to throw in the towel with internet feminism. On some level, I knew it would blow up in my face, and it did.

Some of the critiques were reasonable, but much of what was said about me was, uh, definitely not reasoned. Many internet feminists eagerly jumped on the bandwagon of calling me a slut, albeit in more colorful terms. They claimed I had slept with the man who was their primary cancellation target (I hadn’t) and they left graphic commentary across the internet about my supposed sexual misdeeds (ironic given that we weren’t supposed to judge each other for our sexuality, right?).

Any insult was fair game and no one cared about principles once the feeding frenzy was on. As internet fury mounted against me, I spent three full days crying hysterically. One of those days was Christmas Eve, and my mom tried to get me to go to church, where she was helping with the service; I was unable to stop crying long enough to quietly watch the service, so she had to put me in a back room to cry alone. At the frenzy’s peak, I lost concrete opportunities and money, like a speaking engagement at Harvard. I’d been scheduled to give a talk there, but Harvard folded under the public pressure and uninvited me.

People I thought were my friends, including people I helped establish themselves in the internet feminism world, subtweeted me and made forum threads about me.4 But the worst came from people who didn’t know me at all, who seemingly wanted a punching bag. In late 2011, I broke my neck in a bicycle accident, with a long recovery process. A prominent feminist led a Tumblr thread where people posted their spite about me, full of comments saying my life-threatening accident was hilarious—all while I was in recovery.5

At the same time, when I go back and review it all today, it strikes me how much I disagree with some things I said. Some critiques that adorned my cancellation were correct! For example, a writer named Maia at a blog called Alas! A Blog wrote a response to me at the time. Even back then, I took it seriously; I got it reposted at one of the big feminist blogs to increase its audience. As Maia wrote, “I have known far more perpetrators who were trying to persuade people that they were genuinely trying to change, than those who have genuinely tried to change.”

Today, over a decade later, I relate even more to what Maia wrote. If I’d had more lived experience of abusive relationships back in 2011, then I doubt I would have said what I said. Abusers have huge incentives to lie about whether they have changed, and many of them do. I didn’t understand that before, not in the way that I understand it now. Plus, the backlash in 2011 usefully pointed me to the discipline of transformative justice.6

The most confusing part of being canceled is that it’s hard to figure out which parts are “deserved” and should lead to personal change, and which are unfair. Post-cancellation, I spent a lot of time thinking about this. I pulled myself together and published my book, Confessions of a Pickup Artist Chaser: Long Interviews with Hideous Men. It had been hotly anticipated, and was an immediate success. It hit number one in both its Amazon categories, sex and feminism, for a full week after its debut. During the release, I attended SXSW for the first time to give a talk. There I was invited to a private party for famous internet feminists.

Maybe, I thought, this was my chance. Maybe I wasn’t permanently canceled after all?

When I walked into the party, I was nervous. Everyone in that room saw my cancellation play out over Twitter, Tumblr, and blog comments. I assumed everyone was mad. No internet feminists had reached out with a kind word. Many had been actively mean! But, I quickly realized, they were all super nice to my face. In fact, some of the women at that party told me they were sorry about what had happened, that they’d experienced similar toxic mobs, and that I didn’t do anything wrong. Again, these were people who did not say a thing, privately or publicly, to help me when the cancellation went down.

I felt torn between disgust at the methods of cancellation, and a true desire to learn from my cancellation. And yet I realized, talking to the women in that room, that many of them did not share this desire. Many dismissed the concerns of their own followers.

I realized, too, that many now respected me because I was poised to come back stronger than ever. My book was an obvious success, I had a real audience, and that was what mattered to them: an independent audience was power. What I understood then, on that evening, was that this was not about principles or shared moral convictions, nor was it solidarity. It was basically a private club of powerful women. The baseline philosophy was “might makes right.”

Worse, the club benefited from cancellation. It helped them stay at the top.7 That was the thing that disgusted me so much that ultimately I could not bring myself to publicly rejoin the movement. “The club” let newcomers run into the cancellation buzzsaw while watching to see if they survived, and if the newbies didn’t? Well, then there was less competition for the women in that room! Supporting a canceled feminist was a calculation made afterwards, based on whether she made it through the experience.

I didn’t leave immediately. I went back and forth about it. Was it fair to judge the internet social justice community for its behavior during cancellations, given that cancellations were admittedly confusing? Also, cancellations are often a bottom-up process, though many prominent people devise ways to orchestrate or incite them. So maybe it made sense that leaders were prone to letting them happen. Nobody was in control of the process.

When I tried to think about what might be better, I wasn’t sure. It wasn’t like I had a better system. Selfishly, I was also grateful to have been invited to the party, grateful on a personal level for how some internet feminists, in the end, tried to be kind.

Eventually, I concluded that while I was not sure what social mechanisms would be better, I could not continue participating in a movement where cancel culture was so prevalent. Crucially, I also saw that many of the real-life feminists I knew—women with meatspace jobs that helped women in crisis—felt that internet feminism was interesting yet toxic. So eventually, I published the books I’d planned to publish in 2012 and moved on.

I kept some of my friends from the feminist movement. I generally believed in social justice principles, so I stayed connected, just wasn’t as vocal. I watched #MeToo go down, and despite my distaste for cancellation, I was mostly glad that there seemed to be a kind of justice—finally—for serial abusers like Harvey Weinstein. I wanted people like Weinstein to fear the mob because maybe then, I thought, they would stop hurting others.

Then, in 2020, when I witnessed the Black Lives Matter riots and saw that many social justice people defended the violence, I began wondering if the movement was morally vacant. Plus, cancellation reached new highs during that time, and its penalties were worse than ever. There were examples like Amy Cooper, who was forced into hiding after a dog-related confrontation in Central Park went viral; there was the mounting toll of random and clueless people who lost their jobs for social justice offenses, many of whom were themselves lower-class people of color. The song “Fake Woke” charted in early 2021 because it was a clear representation of public feelings regarding the divisive hypocrisy of it all. It was now obvious that, to many Americans, wokeness appeared pointless at best and to serve the powerful at worst. But what hit me hardest was seeing real violence mount in American cities while many left-wing commentators defended, even glorified it.

I had to finally ask myself: could it be that the social justice movement was making things worse?—or, did too many people in the movement care more about their careers than their principles? That was when I got involved in the right-wing neoreactionary movement, also known as NRx.

I knew people would be shocked by my public shift towards NRx. I had some sense of what it would cost me. But by the time I became publicly affiliated with NRx, I was so infuriated by the social justice left—by its hypocrisies; by its refusal to moderate its extremists, no matter how much harm they do; by its lack of care towards people who needed our help, including people harmed by the riots—that I thought it was plausible the right wing was a better place to invest my energy.

This turned out to be incorrect. Sadly, there were more rude awakenings in store.

Canceled Right and Left

When I dusted myself off post-cancellation in 2011-2012, I tried to double down on friends who seemed less political. I thought they would have better community principles. I spent a long time prioritizing friendship with people who mostly weren’t involved in politics at all. And yet much later, in 2021, when my engagement to Curtis Yarvin was announced, I experienced the same poisonous bullying from a decade ago.

To this day, people sometimes ask me at dinner parties, “Did you really love him?” as if it’s too incomprehensible to be real. For the record, I want nothing to do with Curtis today—you can read my feelings on his New Yorker profile here—but of course I loved him! I was not planning to marry someone I didn’t love!

At the time, I had reason to believe Curtis loved me too, and that he wanted the best for me. When Curtis and I were together, we did all the couple things: we walked on beaches together; we cried in each other’s arms. Curtis called me “the thinking man’s trophy wife,” which I found so hilarious that it was in my Twitter bio for a while. He compared me to goddesses and mythic heroines, and he said things like, “Achilles would rather have you than Troy.” He introduced me to all his friends, said repeatedly I was The One, wrote extensive poetry about me. By the time we were engaged, I thought I understood him. I wanted to marry the man I thought I knew. I was willing to tolerate the immense backlash I got for our engagement because I loved him.

Rightly or wrongly, when we were together, I also saw Great Spiritual Meaning in all of it. I agreed to marry Curtis partially because I believed there were vast mimetic implications to our union. I thought that in our fractured society, there might be a political leadership role played by a couple that could embody a wholly different political philosophy and a sincere truth-seeking effort. So I felt that our relationship was bigger than just the two of us. That made me more willing to cope with the backlash, too.

Just like before, I expected it and it was worse than I expected. For weeks, whenever I opened Facebook, I saw threads of my Facebook friends openly trash talking me or “being concerned about me”8 without tagging me, the equivalent of a Facebook subtweet. I wondered if they knew I was seeing all of this, so in one thread, I posted a comment noting that I could see what they were saying. Commenters on the thread indicated they didn’t care, or that they were even glad that I was reading their comments because they thought I deserved it (although some apologized later).

The most amazing example was when people—some of them people I had collaborated with—started leaving mean comments directly on my Facebook engagement announcement. I deleted most of those comments, but I didn’t delete all of them because I was trying to accept and internalize critique. Nevertheless, when I started deleting some of the negative comments, including comments that said nothing but “ugh,” there were commenters lashed out at me further, self-righteously informing me I was failing to “take accountability” for my misdeeds because I was deleting toxic personal comments from my public engagement announcement. Seriously?

Weirdly, however, the public backlash turned out to be the easy part. My situation had all the same dynamics as when I was canceled in internet feminism, but new dynamics were added: some people tried to get close to me because Curtis is rich and famous, including people who publicly hated him. There were liberals—people who attacked Curtis publicly—who privately tried to find ways to access Curtis (and Curtis’s money and Curtis’s clout) through me. Others exhibited performative fury about conservatives or made moral judgments about me behind my back, then turned around and asked me to introduce them to Peter Thiel.

One time during my engagement, I was hanging out with a friend who oversaw a cultural hub that I loved, and my friend asked me to get Curtis to fund the space. This was wild because Curtis was banned from that space—a fact that caused me frequent headaches, given that Curtis was my fiancé and I spent a lot of time there. This friend didn’t appear to see the problem at all. They genuinely thought it was fine to ban Curtis from their space and then ask me to get Curtis’s money to fund it.9 I had more than one interaction like this.

I was disgusted by the moral flexibility that suddenly appeared when so many of my liberal friends came close to money and fame. I almost preferred the people who blasted cancellation poison. I began to wonder whether only a minority of my liberal friends had anything resembling consistent integrity.

But there was worse to come. During my engagement to Curtis, he asked me to have his child, and then during my pregnancy, Curtis and I broke up in rather scandalous circumstances. Curtis then sued me two weeks after I gave birth, which severely damaged both my health and my personal finances. Eventually I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder from the entire sordid situation.

At this juncture it’s worth noting that people like to speculate about sexuality in my relationship with Curtis. Of course they do. It’s the internet, right? The fact that I have done a lot of BDSM somehow relates to what happened between me and Curtis. This becomes a reason it was okay for me to be hurt so badly. Some of the jokes are funny, I must admit, like the comment suggesting I was locking him in a “BDSM cuck shed” (I was not). But this aspect remains frustrating for me, given my ideals as a sex-positive feminist.

Anyway, Curtis and I didn’t do BDSM as part of our relationship, so all the weird commentary about this is irrelevant. I also think it’s interesting that the single most traumatic outcome of my life happened after I tried to marry a conservative guy who repeatedly insisted that he was monogamous and vanilla. I’ve never had anything remotely this bad happen in any of my BDSM relationships; I’ve never been diagnosed with PTSD after a BDSM relationship either. Indeed, one of the biggest and best-designed studies on BDSM found no broader correlation between abusive experiences and BDSM desires. So, while I am open to in-depth discussions of BDSM and psychology and whatever else is relevant, I’m not sure my relationship with Curtis has anything to do with it.

After I gave birth and Curtis sued me, I was in a position where I had a newborn baby, and I was in a health and financial crisis, and I’d lost some support from my liberal community. I would love to be able to tell you that the conservative community rescued me! But it didn’t.

One thing I’ve heard experts say about PTSD is that the moment of trauma is not the moment of pain. It is the moment of feeling alone with it.

It wasn’t like I thought the conservative movement was perfect. It seemed obvious that conservative leaders were just as bad, maybe worse, at taking audience feedback, compared to what I’d seen in the social justice world. But what I learned after giving birth was that, despite all the public insistence that they care about family and motherhood, only a minority of my conservative friends helped a real, live single mother when I appeared in their midst. And over the ensuing years I saw that many ran a similar calculation as left-wing careerists did. To them, I would be worthy of open support only after I demonstrated that I was strong enough to have a comeback, on my own, without their help.

I’ve often heard “the people who show up in a crisis are not the people you expect.” That was my experience, too.

I met truly excellent people in both of these political movements. Some were precisely the people I thought would help me in extremis, and others people I never thought I’d ally with, but who displayed great strength of character in helping me, even though I wasn’t the kind of person they had any reason to respect or believe. Some Christians have been so supportive of me in my single mother journey. Who would have thought anyone on the religious right would work through their disgust enough to be kind to Clarisse Thorn? I’m grateful for that.

And so as I emerged from this personal darkness and confronted how simplistic my idea of community used to be, my next question became: what would it mean for all of us to support each other better?

What Now?

A phrase emerged in the last decade, virtue signaling. It’s the conspicuous display of ethical or political awareness; a performance instead of action. If you’d asked me fifteen years ago what percentage of virtue signaling correlated with real virtue, I would have said 80 to 90 percent; if you’d asked me five years ago, I would have said maybe 20 percent; today I’d estimate it at, like, five percent. Maybe five percent.

I used to decide who to hang out with based largely on intellect and critique. I used to select for people who could speak clearly about social dynamics or morality. But when the chips are down, perception and eloquence do not, in fact, correlate with morality. I feel like I’m still getting my bearings about what integrity means in a world that feels ever more corrupt, but one thing I know: I respect wise action more than ever, and brilliant words less than ever. Maybe that’s a strange position for a writer, but that’s how I feel now.

From now on I want to do good work, take care of my family, and live a healthy life. And I want to link up with other people who prioritize their integrity too, independent of politics.

I believe we can build better communities that genuinely support their members through experiences like these, and that it will be the work of lifetimes, especially in this lonely era. I’m hoping my history will help me contribute to that goal. That’s one of the silver linings.

Lydia Laurenson is a researcher, editor, and writer, described as a “reporter on the future of the human heart and mind.” Find her work on Substack at Solar Light.

Thank you for reading Season 4 of The Ick! See the full season archive here.

Stay tuned for announcements about the forthcoming print magazine + live reading in San Francisco. Help us offset printing costs and get an advanced copy by subscribing ($0-$250).

Specifically, I was trained as a medical advocate by an organization in Chicago that is now called Resilience. (When I did the training, it was called Rape Victim Advocates.) Sometimes I think “rape crisis counselor” isn’t the right phrase to describe a medical advocate, but I think most people don’t know what a medical advocate is, so hopefully it’s close enough.

I wrote under the name Clarisse Thorn between 2008 and 2013. Years later I voluntarily came out of the closet, in 2018, after I was quoted in the New York Times in an article about the boundary between abuse and BDSM. That article felt like a victory at the time, like there was finally a more honest conversation happening around sex and feminism—a conversation that I and so many others worked hard for. After it came out, I suspected there would never be a better time to come out of the closet, so I did.

Yes Means Yes was edited by Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti. I did not contribute to Yes Means Yes, but the book had a spinoff blog, and I contributed to the blog several times after the book was published. The blog archive is still available even though the blog hasn’t been updated in a decade, which is nice; many blog archives from that era are gone now.

In the mid to late 2010s, after the events of this story, I did some NGO work on gauging the harms of social media technology. Most research in that area is nonsense, but one finding that is *not* nonsense is this: “Cyberbullying” is notably worse, and has a bigger emotional impact on its targets, than in-person bullying. I don’t think our society has caught up to this.

Years later, circa 2015, after I had moved on and was working in the field of media innovation, I attended a community event at a prominent university where we workshopped ideas about internet community moderation. The event was partly moderated by this same prominent Tumblr feminist who had mocked my injuries. She was honored there as an exceptional internet community organizer. She did not know who I was and I did not tell her. Nor did I try to explain what had happened to anyone else, aside from a brief comment to one of the men who organized the event with her, whose blank-faced response made it clear he had no idea what I was trying to warn him about (I assume that over the ensuing decade he found out).

I feel like the fact that the journalism industry deliberately recruited and honored “internet community innovators” who were skilled at ringleading vindictive cancel mobs explains a lot about what happened to the industry over the next ten years.

Interestingly, as I became less involved in feminism and later moved to the Bay Area, I became more involved in communities that actively workshopped transformative justice processes. Eventually, over a decade later, when I launched my magazine, the longest article in Issue One was about transformative justice. (It was edited by yours truly and written by a white man; he was the person available to write it and passionate about doing the work, and I think he did a good job.) So I am grateful to the people who took the time to send me information about TJ, because my later community work would have been different without their efforts.

Jo Freeman touches on this in her epic 1976 essay about the seventies version of cancel culture, which she called “Trashing.”

The reason I put the words “being concerned” in quote marks is that these people, who expressed public concern and received social media applause for it, were not, in fact, hugely concerned about me. I know this because when things fell apart for me later and I became a single mother with PTSD, *not a single person* who publicly posted about their “concern” during my engagement reached out to me or helped me. In contrast, I got concrete help from friends who had expressed concern *privately,* and I also got a lot of help from friends who didn’t say anything publicly at all. So public posturing about “concern for Lydia” was a negative correlation with helping me when I needed it.

To be clear, they did not offer to un-ban Curtis in exchange for Curtis’s money. Does this make their request more morally acceptable, or less so? Who knows!

A big reason I never got involved in any left-wing activism in the last decade and a half (it would have been a great way for a nerdy hetero guy to meet the opposite sex) was this tendency to dig up random transgressions from 10 years ago, and the ever-changing list of transgressions. Plus if you're kind of awkward it's way too easy to accidentally commit 'harassment'.

I've since drifted right, but there are issues on which I still lean left.

I share some of your concerns about cancel culture, and I think RJ/TJ that truly grapples with what it means for humans to make mistakes and cause harm (because we all do) is really important, much more important than virtue signaling righteousness, but it really still strikes me that in everything you have written about yarvin and NRX you do not seriously grapple with the fact that these people are actual fascists with actual pipelines to power, and are more dangerous than woke people on the Internet. I am sorry for the harm they caused you personally, but I'd like to see you write something about the harm they are doing nationally, which is actually, materially dangerous.