The Politics of Contagion

Dispatches from the immune system of a failed utopia

Welcome to The Ick, Season 4: DISGUST. This season I’ve invited a brilliant cast of writers and friends to explore what makes us recoil and why.

Season 4 will culminate in a print magazine and live reading in San Francisco. Subscribe here so you don’t miss event info and updates. Every paid subscription helps us cover printing costs.

Now, over to deepfates…

I’m one of those people they call “extremely online”.

I’ve made something of a craft out of going viral. And I think people don’t understand how much our politics and culture are defined by the very 21st century dynamic of virality. In the sense of popularity, sure, but also actual viruses like Covid or emotional contagions.

I wasn’t always an internet person. I used to live in a different hyperconnected bubble, a much smaller one. I spent three years at an off-grid commune deep in the woods. I was there because I wanted to experiment with radical social structures. I definitely got to do that. I weathered several years there, and learned a lot of things in that microcosm that have helped me navigate the internet age.

Let me tell you the story in three plagues.

Body without organs

I was hoboing across the States, playing guitar, when I ran into some friends doing similar shit. They said, "We found this old hippie commune at a ghost town in the mountains and we're going to go live there and take it over. You wanna come?"

Naturally, I said yes, and my friends and I hitchhiked into a thundersnow to get to this incredibly remote place. When we got there, we discovered six other groups of people with the same idea. There were only so many cabins and there were a lot of people, and not everybody liked each other. So we allied into tribes, sorting against each other through a logic of mutual disgust.

The people that brought me were radical feminist primitivist witches, so I was inducted into their cabin—a gender-flipped Wendy and the Lost Boys kind of thing. But it meant I would never get along with the weed-grower flat-brim deadhead faction, or the Marxist pickup truck rifle guys. Instead we allied with the Maoist peanut butter commune refugees.

The hippies who had set the rules decades before had all left, and not written down the things they’d learned in their time, so we had to reinvent lots of things from first principles. But they did leave us with one huge, permanent constraint: the open door policy. The motto of the land was "free land for free people," and that meant we always had a slow trickle of new people showing up. Anyone could try to live there, and be considered a member until proven otherwise.

So we were one social organism, theoretically, trying to take care of each other and build a functioning micro-society a hundred miles from actual civilization. We thought of ourselves as pure, in a way. We had isolated ourselves from society. We could no longer be infected by it—so we thought.

Staphylococcus aureus

The first summer we all got staph.

Someone had arrived with infected wounds, their immune system not strong enough to fight off these flesh-eating bacteria. This isn’t a hippie thing, staphylococcus aureus lives everywhere, on any surface, even in the city. But maybe they brought in some specialized medically-resistant variety. The rest of us were mostly healthy, but not particularly clean. We shared one communal shower, and one communal towel. It quickly spread to us all.

It was summer. We all had mosquito bites and little scratches. That's how it is when you live in the woods. But now they didn’t heal. Instead, the bacteria was fizzing away in there, eating the edge of the wound outward, making it soft.

I started to feel kind of sick one day, and looked hard at one of my scabs. It looked sort of wet and puckered, like skin after a long bath. The next day all my little wounds looked like this. A few days later, it was worse. From a scrape on my shin I could see this angry red line of inflammation crawling up my leg—my blood had started to get infected—the evil was climbing toward my heart.

We had a well-stocked “medicine room” but only a few jars of old expired antibiotics. Those went to the worst cases. The rest of us tried healing it with herbs. I remember spending three hundred-fucking-degree days just hanging in a hammock, sweating and hallucinating from massive amounts of garlic and goldenseal and top-grade California hashish.

One guy actually had to have his lymph nodes removed—they liquefied in his armpits. He survived only because we took him to a hospital in the city, and they were legally required to treat indigents with no health insurance or money.

The worst part though, was the way it infected my mind. I felt like it was turning me evil. Oozing from many wounds, shambling around in the heat, surrounded by buzzing flies. I remember standing in the dinner line and wanting to eat my fellow comrades. Thinking about gnawing on their succulent flesh. Mouth watering at the image of a sizzling human drumstick. Suddenly thinking how very far away we were from society and its taboos.

After those three days in the hammock, I made it through. Ask me sometime, I’ll show you the scars. But I’ve never told anyone about the flesh-eating thoughts.

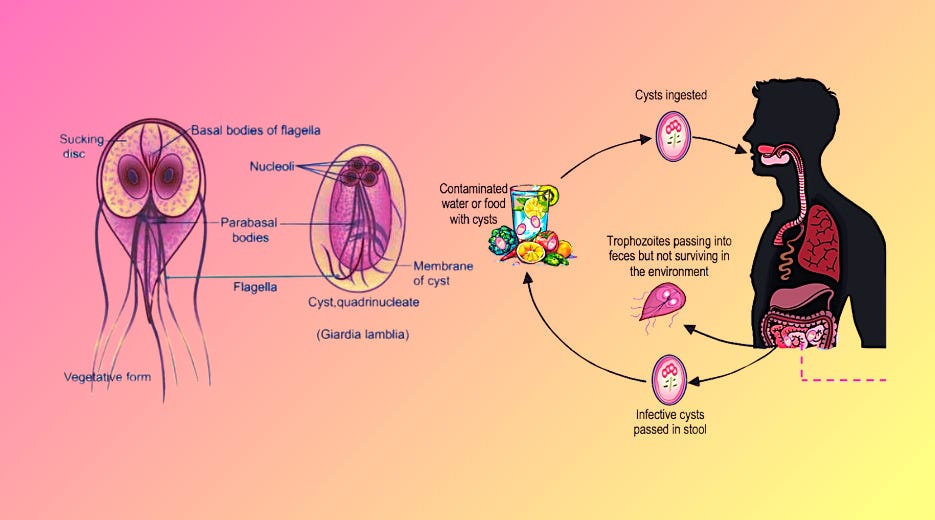

Giardia lamblia

Another year we couldn’t stop shitting ourselves, and didn’t know why.

We couldn’t find the culprit for weeks. We checked the drinking water filter and the hand soap, we cleaned the building, we made the primitivists move their roadkill tanning farther from the kitchen. But it wasn't enough. We kept getting sick. We learned later it was giardia.

Giardia is like a little tiny sucker fish in your stomach—not really a fish, it's a microorganism, but it latches its mouth onto your intestinal wall and sits there absorbing all the sugars and nutrients you would otherwise eat, and outputs the results of its metabolism. That means that it’s eating your food and shitting in your guts. They produce a lot of gas too, which has to come out somewhere, so all day long you’re burping out their farts.

No matter how much we washed our hands or cleaned our dishes, everyone kept getting sick. Sometimes we would recover for a minute and make a big decadent carrot cake to celebrate. Then we would all get sick again, shitting everywhere, spreading more of these critters back into our communal body. We learned later it’s the sugar that helps them multiply. Ass to hand to mouth to guts to ass, that’s the life cycle of giardia. And they were thriving.

Every night I'd wake up knowing I was about to peanut butter my long johns and have to run through the woods, knees akimbo, trying to make it to the outhouse in time. One time I saw ghosts in the field but I couldn't take time to stop and talk to them. They shouted and waved me over. There's nothing I'd want more than to ask some ghosts what they're looking at in an open field under the full moon. Were they real? Was I delirious from a complete lack of ability to absorb nutrients? Either way I missed my chance.

Finally somebody walked the ditch for the first time in a while, to clear leaves and debris. We rinsed our dishes with the water from this ditch. And lo and behold, in the ditch far upstream, was what used to be a bird. A Stellar's jay, melted by time. It had degraded and poured its mortal flesh into our water supply along with all the bacteria that grew upon it.

This was the life support system! The very technology that is supposed to enforce hygiene, transformed into a vector for contagion.

When we finally recovered we had all lost many inches on our belts. And I never fully trusted the dishes again.

Becoming-scabies, becoming-wolf

Then, the scabies.

An image I will never forget. My friend came to me in the garden. Summertime, we were working. He said, "I need to talk to you about something." He unbuckled his overalls over his bare chest and dropped them to reveal…his balls, all scratched up and swollen like a pound of ground beef. I said something supportive like "Oh God!" and jumped away. He said, "Yeah, I don't know, man. It's so itchy."

By now, I’d had my share of itches. After the plagues of staph and giardia, I knew we were one communal body. I said, "All right, let's figure it out. Does it itch in the daytime or at night? When it's warm, when it's cold?" We shortly determined this had all the patterns of scabies.

Scabies is a mite, like a microscopic eight-legged crab thing. You get it from other people, or clothes or surfaces those people sat on, and then they live inside your skin and burrow around like some kind of Mars colony. They make these telltale tunnels from one spot to another, and you can see and feel them living inside you, digging around.

Only this didn’t have the telltale trails. Just spots. “That’s why I let it get so bad,” he said, “because I thought it can’t be scabies. Right?”

And as we looked at his balls, looked at his other body parts, I thought it's gotta be scabies. I just knew it. This made me start to worry about the bumps on my hand. The itchy bumps, which I had been thinking were mosquito bites or poison oak—well, they sure do look a lot like scabies without trails.

So immediately upon becoming aware of it, I was infected too. I didn't even touch him, but just the knowledge of this infection jumped from him to me and now this was my problem too.

And because I had scabies on my hands and my buddy had scabies in a much more sensitive place, I was now the person to announce to the commune that we had a scabies problem. The immediate response: "Maybe you do, but not me."

So then I was the infectious one, a scapegoat for the community. I said, ok fine, maybe it’s my fault that everyone got it, everyone can be mad at me if they want, we just need to admit it so we can start making it better. One by one, people admitted they’re itchy too, until it was obvious that we all had scabies. Because clothes and couches and towels, we shared all those too. So we all had to deal with it together, as one communal body, a body infected with mites.

Well, how do you get rid of such a thing? You can’t do it with herbs. This required modern science.

We went down to the city and asked a doctor. The prescription was expensive for this chemical, permethrin, a pesticide extracted from a chrysanthemum. But you can get a very similar dilution of permethrin in a much larger bottle for much cheaper at your local drugstore. It's called flea dip for dogs.

So then we were staying at a friend-of-a-friend’s trailer at the edge of town, having to flea dip ourselves two by two in the tiny bathroom in the heat. Covering ourselves in a chemical made by a flower labeled “for dog use only,” we started barking and yipping at each other, howling at the absurdity of this crowd soaked in flea dip in a trailer bathtub. We growled and woofed and snarled, we became werewolves.

Despite the fact that most of us hated each other, we were stuck together in one communal organism. There was no barrier at the edge of any one of our bodies—we were all far too dirty and too cuddly for that to work. The edge of our body was at the edge of our village. The barrier was between us and society, and we were now something outside of it. Infected by the mite and the flower and the wolf. We were transforming, becoming plant, becoming animal, becoming bug, becoming ecosystem, recognizing that we were all one, permeable. The flies and the communal towel and the pit latrines and the heap of dishes to be washed by hand in lukewarm water, they connected us as one body. We were a system of flows.

After we had been through all the werewolf stuff, washed all our communal bedding in the gigantic cyberpunk laundromats of Southern Oregon, we went back to the woods. One day we had a visit from the greater family, the nearby hippies that had once lived there and were still involved with the land.

One of them told us, "I remember the first time we had the scabies with no trails. I think I brought it from Boston in '68. And then I gave it to several of the guys I was sleeping with at the time. Funny to think it's still going around."

If we had thought to recruit more of the social immune system, we could have got this information from deeper parts of the body politic. We would have been more disgusted, sooner, and rejected the parasites before they took hold.

Semi-permeable membrane

Staph, giardia, and scabies in less than three years. Eventually I realized that these plagues were not coincidence. They were an inevitable outcome of the conditions. An organism is only as strong as its boundary layer. A society is much the same.

Our social organism was too open in some ways: the open door policy meant that all types of people could come in. All types of animals, diseases, and ideologies too. Our governance system was by consensus of those present, so as soon as you show up you get a vote. This made the governance completely impossible, as weekend warriors squared off against the people who would actually have to enact whatever decision was made.

We were too closed off as well. So far away in the mountains, with so little connection to the world, we lost immunities to things in the default world. When I returned I was disgusted by advertising, fluorescent lights, saran-wrapped foods, and all the other tissues of our modern technoleviathan. They were repellent to me, viscerally made me sick. I still think this is the correct reaction, but I’ve grown used to it now, and can stomach the grocery store with a smirk.

An organism must have a semi-permeable membrane. The ability to kick things out if they threaten its health, and the ability to intake resources to survive. Disgust is the immune system of the greater social organism. It protects us from contagion. But in a planetary society, we are constantly exposed to new vectors of change. Foreign organisms, environments, ideas; our cultures and societies are fully inflamed around these perceived intruders.

I see this online all the time. I watch as memetic phrases and viral emotions spread through my networks. We attack each other for following the wrong person on social media, for not wearing masks, for being inoculated with RNA, because we are all in constant fear of infection. No two groups can ally without first solving every small difference between them. Even homogenous ideological blocs tear themselves apart with loyalty tests and purity spirals. We are in a great autoimmune spasm of the human species.

If we are all one planetary social organism now, that creature is in pain. Its own organs attack each other, unable to recognize their interconnectedness. We’re constantly putting up boundaries. Boundaries between nations, between computers, between people.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

I’ve learned a lot from experimenting with radical social structures, both in the woods and on the internet. At the commune, I thought we could prototype methods of living that were more egalitarian and ecologically balanced, and then export them past the barrier of our village to replicate. Those experiments were mostly failed utopias.

But I learned something important there, something I believe needs to spread and take hold: not all contagion is destructive. The flower feeds the bee and the bee pollinates the flower; neither can exist without the other. We are not separate species who must fear infection by the other. We are a system of flows.

deepfates is an writer and AI researcher. You can find him on the internet.

Further reading

A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

I’m sorry maybe this makes me a hater but, for real, were there no people who grew up rural among you? Washing dishes off in ditchwater…c’mon. The following giardia is such a pure allegory for hubris.

I also have spent time in public health, albeit in a less applied way ( https://open.substack.com/pub/lydialaurenson/p/the-time-i-joined-peace-corps-and )

and it also influences my thinking about online virality and the flows of ideas. This is a great piece, thank you for writing it and I hope we get to talk about it in depth sometime :)