How to Hear

Does music theory improve listening? with @soundrotator

I was lying on the floor weeping. The concert venue was packed. On my back, I stared up into tendrils of dry ice fog. My eyes blurred through tears of joy. I asked myself, What the hell am I hearing?

The floor underneath me was shuddering. I felt the bass wobbling in my body—in my stomach, in my chest, in the liquid that cradled my eyeballs. The corners of my vision fluttered with the subwoofers.

The crowd had started on their feet, clapping politely, then began slowly melting away as Tim Hecker, the performer, tilted and quaked the room with his music. As the fog filled the space, Hecker became a dark blob onstage, and my fellow audience members spread out, receding into different depths of obscurity. We reached for the floor, crouching, kneeling, splaying out as Hecker’s throbbing soundscape buckled the ground underneath us.

Unsteady, I reached for the earth, laying prone against the felty carpet. I was melting, I was floating, I was exploding and reconfiguring. I felt tears leaking down the side of my face into my ears. Lasers in red and blue sliced the fog into sheer planes of light.

This was the MUTEK Festival in Montreal, and it remains one of my most cherished music memories. Hecker’s work has been described as “structured ambient”, “tectonic color plates” and “cathedral electronic”. He describes it as the intersection of noise, dissonance, and melody.

The experience was transcendent. I felt rearranged on a molecular level. It wasn’t just loud music in a foggy room, it was an atomic cleanse, a spiritual wringing out. This is what the album reviews are missing, I thought.

Before that moment, when I told people I was a music journalist I felt like a liar. I didn’t have a music degree or play an instrument. But weeping on the floor with Tim Hecker showed me I had an edge. Music journalism needed less heady talk of production value and chord progressions—it needed transcriptions of the human experience, the musical response in the body.

Over the next five years, I wrote about the bodily euphoria and collective effervescence of music, and honestly I was really good at it. (Read about my controversial music journalism career on Season 1 of The Ick). Live music helped heal the loneliness of living in a desolate foreign tundra (Canada), and tap into my mind/body connection (get laid).

But I’ve always wondered what it’s like on the other side. Do music theory scholars experience listening differently? Does one’s quality of hearing improve with technical knowledge?

How Theory Helps

Rebecca P. is a choral director, composer, and pianist—you may know her as @soundrotator.

Growing up with a music theory professor mother, Reb has never not known the mechanics of sound. She started piano lessons at age four. When she hears a song, her fingers move across phantom keys, working out the melody. If she hears an ambulance siren wail down the block, she can name its interval and pitch.

Music theory, she says, gives you ways of understanding music in a precise, mathematical way. It helps you understand the “why”.

“If I listen to music and I'm like, ‘Oh my god, I love this chord progression,’ I have this immediacy of hearing what happened mechanistically,” she said. “And I can be like, ‘Oh, that’s why it made me feel this way.’”

Reb can listen to a chord, hum its component parts, rotate it in her mind, and pluck each string in her imagination. Sure, her ear is tuned to understand why the minor feels sad, why sharps feels uneasy—but she can also hear the red of a rose and the bittersweetness of heartbreak.

She shrugs off too much praise, though. She argues that a little knowledge goes a long way. And the miracle of anatomy does a lot of work for us.

Take the human ear, for example. The dish of your outer ear funnels the frequencies of plunked strings down a canal. There’s a tiny, perfect drum there—the tympanic membrane—that happily thrums to the rhythm. This vibration is amplified by your smallest bones: the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil), and stapes (stirrup). Your body’s miniature percussion section sends ripples, like a skipped stone, across a tiny reservoir of fluid. The movement compresses the stereocilia, hair-like anemones on the ocean floor of your cochlea, creating electrical signals that travel along the auditory nerve to the brain.

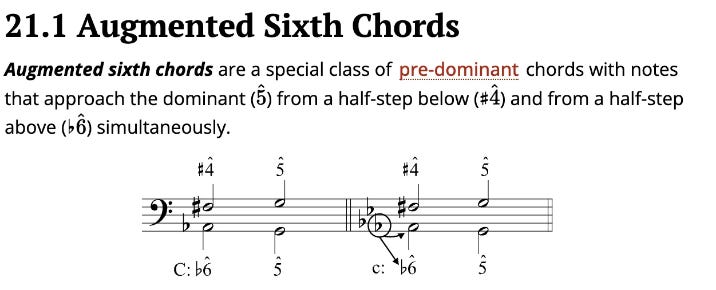

These frequencies have mathematically complex patterns that stir emotional centers in the brain. The European augmented six chords, for example. Reb said, they “hit you in the fucking face.”

“It’s really weird to have a flat six in a chord, and it's kind of is theoretically incomprehensible. When you first learn about this chord, you're like, what the fuck is this doing?”

All types of augmented sixth chords contain a flat six, and a sharp four, notated like this: ♭ˆ6 #ˆ4. (Reb checked my work, don’t worry.)

“The sharp four has that tension that raises up to the five. That one stays really stable and the flat six resolves down to the five,” she said.

“Tension” is a music theory word that anyone can feel. The tension of a dissonant chord is both mechanical and emotional. The frequencies are out of sync with each other, the peaks and troughs of the waveform crashing against the eardrum chaotically. It’s unpleasant. It’s tense. You’re hoping it will “resolve” to consonance, where the frequencies move in sync with each other. In physics, consonance is described as a stationary or time-stable waveform. It feels pleasurable, smooth.

“The augmented six comes when you don't expect it,” Reb said. “It just slides ever so slightly outward from this dissonant interval to the octave. It leads you to a lovely dominant chord, which can take you home to the tonic—and it's love.”

I like the description of chords as “home” and “love”. Reb’s appreciation of the augmented sixth points to the biology at play. The human brain is actually wired to process consonant sounds in one part, and dissonant sounds in another. Biologists theorize this is an evolutionary phenomenon. Our species is specially attuned to the frequencies of the human vocal folds, in order to recognize each other quickly among the dissonant and non-regular sounds of nature (rushing water, thunder, lion’s roar, etc). Biologically, we prefer sounds that resemble our own voice. The notes we find consonant and pleasurable are correlated with the scales of the human vocal range.

So even if you didn’t grow up with a music professor parent, it’s reassuring to remember you are biologically predisposed to understand dissonance and consonance. Moreover, you’re really good at remembering it, too.

The brain is impressively plastic when it comes to hearing and remembering music. Your auditory cortex literally grows every time you make an effort to listen and learn. Even light study of musical tones shows hyper development in auditory regions of the brain. Music researcher Norman Weinberger explains it simply as, “Learning music proportionally increases the number of neurons that process it.”

Weinberger’s own studies have shown that “tuning” the brain to recognize certain tones as significant is “remarkably durable” and may help explain why we can reliably recognize a familiar song decades later, even in a noisy bar, or after suffering memory loss in old age.

How Theory Hurts

While knowing the augmented sixth can be helpful, Reb warns that too much theory can get in the way.

Intellectualizing can become a “sneaky substitute for relating and listening” she said.

“Reading music can be such a complex cognitive task that a lot of people are not actually listening,” she said. “They can describe the mechanism, which does a really good job of convincing someone that they’ve listened, but often they're just looking at a piece of sheet music.”

Obviously, I don’t know what that’s like because I don’t read sheet music. But it seems right based on vibes. Mixed meter, polyrhythms, nested tuplets? The complexity of music theory makes my head spin. The piano acts as the calculator for an immense array of factorials and inversions. So I can imagine that focusing on these intricacies could cloud the why.

“I think it’s beautiful to want to intellectually understand,” said Reb. “But you can intellectualize music in a way that's meaningful and doesn't make the emotional part so remote.”

Listening, she says, has an element of emotional mystery that is precious and easy to lose with too much study.

“I can definitely recall in my teen years being totally mystified by some chord progression or sonic experience. And there's something beautiful about being able to access that mystery and just to let it be a mystery.”

So how do we really listen without over intellectualizing?

“Recognize that the tools of explanation are tools. They're not reality, they're not truth in itself,” Reb said. “You don't have to deny the tools to save your wonder, because life is still mysterious.”

How to Listen

Reb taught me that deep listening is separate from analysis. True listening is pure presence. It’s an act of meditation.

“Listening has a quality of acceptance of the fleetingness, while at the same time really following time really closely,” she said.

This kind of skill doesn’t come easy. Reb is a talented performer and composer, but early in her career she had to overcome severe performance anxiety. Anxiety that she attributed to a lack of listening meditatively.

“If I missed a note, my ear would still be listening to the mistake,” she said. “I'd be 12 measures past what I did wrong, but I was still hearing my failure, or anticipating the next.”

The fix, she said, was a Buddha-like acceptance. She described a vibrant awareness that flows in time with the music, where each note reminded her of her nowness. “There’s a real-time richness that you can follow everything and also accept that it is gone when it is gone, and accept the welcoming of the new thing as it's coming.”

This quality of listening carries over into other parts of life. Reb said this type of meditative listening can be radical in relationships.

“In a conversation, often we’re trying to contextualize what they're saying, make judgments, trying to draw out the conclusion,” she said. “But we can actually just accept what they're saying as it's happening without anticipating.”

This creates space and presence that is deeply nourishing. “To have the treasure of someone just listening and hearing you, it’s life-altering, it's beautiful.” The psychological effects are profound. Social science is finding that “feeling heard” creates outsized improvements in self esteem, openmindedness, and relationship resilience.

However, listening like this is really hard. Our brains resist it. Anyone who’s tried meditation knows our minds jump around frantically drawing patterns and meaning. Predictive processing is important for us as apex predators, sure—but it really fucks with our ability to drop into the time stream man.

Meditative listening takes practice, just like meditation does. But tuning into the body helps. “You can just be present with the infiniteness of the complexity of what someone is saying as they're saying it,” Reb said, “and that feels very much in the body.”

Whether you’re listening to music or a friend’s confession, tuning into the “infiniteness” and “complexity” happens in the body first. We become powerful listeners when we are radically present, without judgment. Instead of anticipating or jumping to conclusions, we just simply hear them. And the same goes for music. Reb said that your relationship with music can radically change if instead of anticipating, analyzing, or explaining, you simply feel it. Music is a waveform, a sensation.

“Sometimes for me, that means going to some really grungy punk show and moshing,” Reb said. “You can go straight to the transcendent, shoving your body into people. Just go jump up and down and find it in your body.”

When I was with Tim Hecker in the fog, I was so overwhelmed by the experience I couldn’t make any sense of it. And that actually helped me “put down the tools” as Reb would say. I just laid on my back and felt it: the rush of the music in my body, and nothing else. I was listening meditatively, without attachment, tuned into the time-independent waveforms of consonance.

There’s no doubt I’d experience music differently if I was listening for the sharps, flats, or augmented sixths. I’m jealous to learn that even a little music theory lights up more parts of the brain as you listen. That feels like something I’m missing out on. But talking to Reb reassured me that music is indeed felt in the body first, before we intellectualize it. And it’s okay if it stays there, as a sense memory, stored in the body.

Instead of asking why, I’m practicing just being present. Listening without judgment or anticipation. Letting my ear bones thrum and my auditory nerve pulse. And if I’m ever struggling, I take Reb’s advice to put down the tools and “find the common sense experience.”

“What is the shape of this music in my body? Where do I feel it?” Reb said. “Start from there and then let it shake loose and expand outward.”

Stay tuned for the full conversation with Reb, publishing next week! Did you miss episode one of the five senses series? Read the How to Feel essay, and watch the How to Feel podcast/video interview.