A Very Brief History of Chivalry

Distortions and adaptations of a powerful mythos

Last week I wrote about the revival of chivalry among trad men of the internet. It’s a part of a wider conservative backlash against gender fluidity—but also a response to genuine confusion many men feel in a nonbinary world. In the article I argue that the Christian warrior-nobel trope is just that—a trope. In fact, it’s a complete distortion of chivalry’s historic basis.

Here are my favorite highlights and historic cliffsnotes that illustrate how chivalry has evolved over time. I’m not a medieval scholar, so if you have qualms with my timeline kindly put your arguments in the comments to boost me in the Substack algorithm.

Our journey starts in the late 8th century. This tumultuous period was characterized by fragmented European kingdoms, the rise of Christianity, and early feudal/agrarian economies…

Feudal warriors

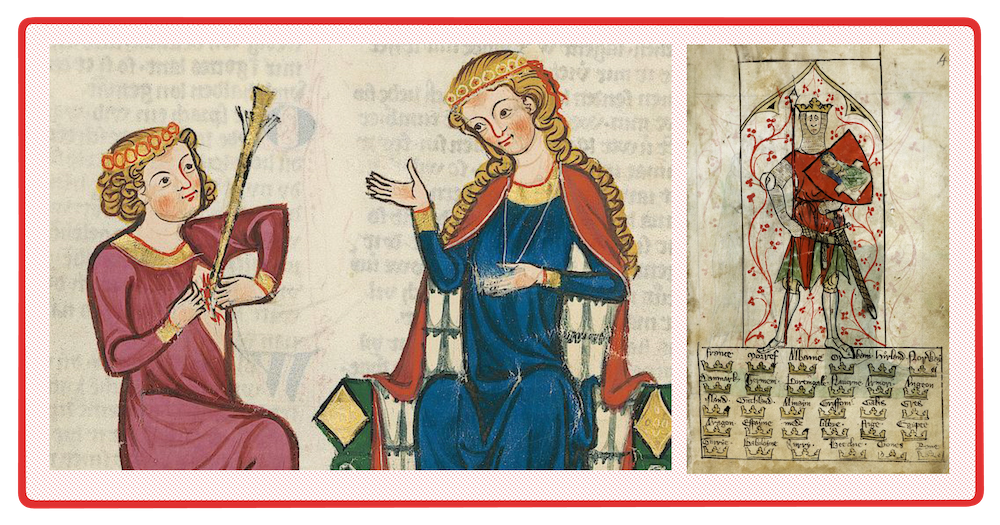

The knight-protector emerged under Charlemagne (742-814), as Frankish kingdoms relied on heavily armed cavalry to defend against Viking, Magyar, and Saracen invasions.

By the 10th century, these warriors had spread across Anglo-Saxon England and Norman territories, becoming integrated into the feudal system, where lords granted land (fiefs) to vassals in exchange for military service.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, the Church sought to temper the violence of knights through treaties like the Truce of God (1027), imposing a code of ethics promoting loyalty and mercy. The loose code decreed no violence on Sundays and feast days, and that knights take hostages instead of slaves, ransom the nobles instead of assassinating them, and spare women and children.

Crusades

The transformation of knights from warriors to "holy warriors" came with the First Crusade (1096-1099). When Pope Urban II called for knights to reclaim Jerusalem at the Council of Clermont in 1095, he offered an irresistible package: spiritual redemption, wealth, and status.

This unified knights under a common Christian mission, elevating their role above the petty power struggles between feudal lords.

Tournaments

In the 11th and 12th centuries, tournaments emerged as training grounds and public spectacles for knights. These mock battles allowed knights to hone their combat skills while showcasing their prowess to potential patrons.

Tournaments became a cultural phenomenon, blending martial discipline with grisly entertainment, with jousting as the main event. Tournaments were increasingly codified over time, transitioning from chaotic melees to highly ceremonial jousts by the 13th century.

Troubadours

Literature played a crucial role in mythologizing knights and chivalry. Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136) established Arthur as Britain's legendary king. Chrétien de Troyes, writing in the 12th century, introduced the romantic elements like the Round Table, Camelot, and the concept of courtly love. Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (1485) later refined these tales into their definitive form.

These troubadours incorporated elements of pre-Christian Celtic myths, such as magical swords (Excalibur), enchanted realms (Avalon), and heroic quests. Figures like Merlin have parallels in Celtic druidic traditions, and the concept of a "once and future king" is borrowed from Celtic beliefs in cyclical time and heroic return.

As the feudal system began to stabilize and centralize power, knights increasingly served in courts rather than on battlefields. This shift caused the codes of chivalry to evolve in the direction of courtly manners rather than martial law.

Decline

Advancements in military technology, like firearms and cannons, rendered heavily armored cavalry less effective in the late 15th to early 16th centuries. The Battles of Crécy (1346) and Agincourt (1415), and the broader Hundred Years’ War, highlighted the vulnerabilities of mounted knights. The rise of mercenaries and professional standing armies signaled the end of their dominance on the battlefield.

Also, important economic changes following the bubonic plague (1347-1351) disrupted feudal structures, and monetary payments replaced land-based service.

Victorian revival

Four centuries later, the Victorians (1837-1901) developed a fascination with medieval culture.

During the Industrial Revolution, progress brought mass production, railroads, and electricity, but also polluted cities, grueling working conditions, and stark wealth inequalities. Victorians also felt a rising anxiety about secularization and moral decay. Medievalism offered a sense of stability, spirituality, and moral clarity that seemed lacking in their modern world (sound familiar?). Writers like Alfred, Lord Tennyson in Idylls of the King (1859), and artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood reimagined chivalry as a romantic and moral code rather than a martial one.

The Gothic revival in architecture echoed this nostalgia, presenting an idealized and sanitized vision of the Middle Ages. This romanticization of chivalry deeply shaped modern notions of gentlemanly behavior and heroic virtue.

In conclusion: chivalry is a powerful myth. It’s inspiring and resilient, and has survived millennia of revisions and adaptations. Whether the modern revivalists succeed in redefining Camelot for the 21st century or simply borrow from its aesthetics, one thing is certain: history repeats, even if it’s just for the memes.

You’re reading Season 3 of The Ick. The social rulebook has been rewritten in our post-pandemic world—and it's left us wondering, “Am I doing this right?” Season 3 of The Ick is creating a modern field guide to social etiquette and decoding the hidden architecture of human connection. Subscribe here. Find season 1: embarrassing stories here, and season 2: the five senses here.

fuck yeah, that’s my boy Charlemagne!!